Knights of the Old Republic

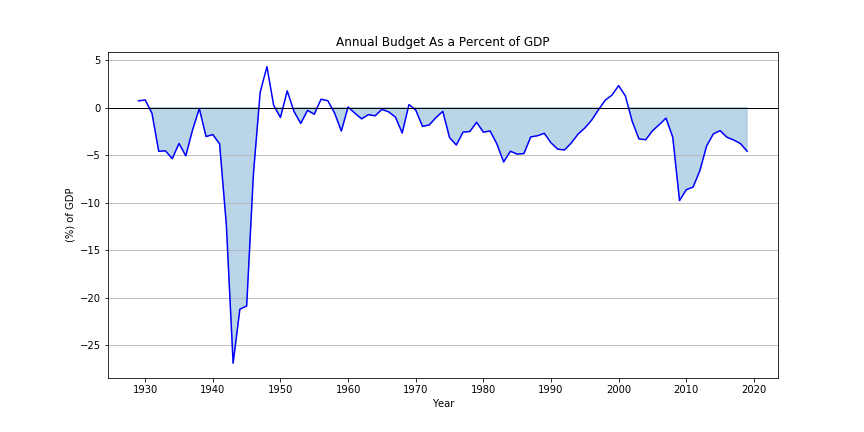

In the before times, people actually cared about the government deficit. Which may seem hard to believe now (see below). For a brief moment there was even a surplus during the late 90’s. Fiscal discipline is one of those quaint ideas right out of a Ken Burns documentary. However, ideas and principles only matter when people decide that they matter.

“I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president or the pope or as a .400 baseball hitter. But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.”

James Carville, Democrat Political Strategist

“Bond Market Vigilantes” is a term for bond investors (usually institutions) who signal to governments that their financial situation is out of whack and that they need to get their act together. They do this by selling the government in question’s bonds. Which drives interests costs up (yields) and makes it more difficult for governments to borrow and finance themselves. Since government bond returns are based on the fisher equation:

The insight here is that your return on government bonds (in countries that control their currency) is the nominal rate minus the inflation rate. The thing the vigilantes are concerned with is inflation. So when the market catches a whiff of policies that they perceive to be inflationary, they quickly dump the bonds in an attempt to bully the government to get a grip.

The term bond market vigilante is admittedly cringe and reeks of inflated self importance. As far as finance goes it’s cringe is second only to “angel investors” those heavenly check writers financing payday lending on the blockchain. The bond market vigilantes see themselves as the enforcers of fiscal discipline. The knights of the old republic protecting states from themselves who would deficit spend like drunken sailors given the chance.

The vigilantes flexed their muscles most notably during 1993 and 2010 in the United States and during the Eurozone crisis from 2009-2012. Interestingly enough in the United States, they both occurred shortly after Democratic Presidents took office. Which is interesting considering that the Democratic Party has a better track record of fiscal discipline. The vigilantes are more a political expression by investors and supported by the credit agency’s which isn’t surprising that they favor conservative policies given the political leaning of the industry.

Credit Ratings

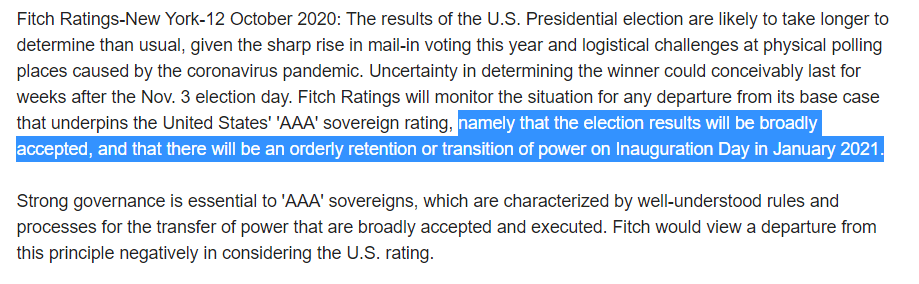

The credit rating agency’s are a good idea in theory. Independent entities evaluating the creditworthiness of companies and governments. Adding credibility to markets and allowing investors and regulators to make quick judgments without having to do their own research. But anyone who has done 5 minutes of research knows you cant really rely on their analysis. Then why are they so important?

The three major credit agency’s: S&P, Moodys, and Fitch provide credit ratings for governments and companies. They analyze various factors to determine the likelihood of default. Their analysis is never perfect and they famously missed: Enron, sub-prime mortgage backed securities, P.I.I.G.S. debt prior to the Euro zone crisis. In addition, when S&P downgraded U.S. Debt in 2011, it later came out that they made a $2 trillion error in their revenue projections. When pressed on this mistake their rationale changed from poor financials to be “political stability.” The ratings agency’s may be able to identify firm specific credit risk, but like every other institution they are unable to identify/prevent systemic risk. The incentives are such that their ratings come with a political concern as well (See above and below).

Credit ratings primarily serve as a means for bucketing bonds into different categories for potential leverage application. Banks and insurance companies use the higher quality credit as collateral to borrow short and lend long. This was the critical tipping point in the financial crisis as most mortgage backed securities were highly rated at the time were used by banks as collateral and when they started to trade around like the junk bonds they were, some banks did not have enough liquidity. We all know what happened next.

Where are we now?

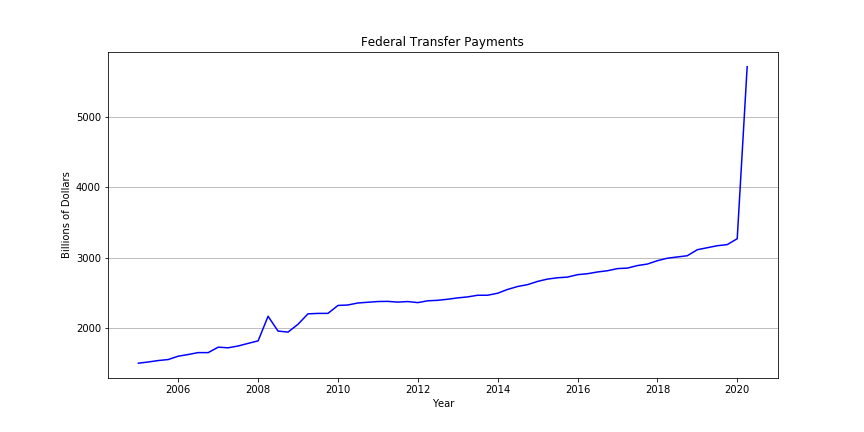

The coronavirus and the recession that was induced broke every macroeconomic chart. Transfer Payments and government expenditures have exploded this year due to the tremendous amount of federal stimulus. As you can see they are basically the same chart.

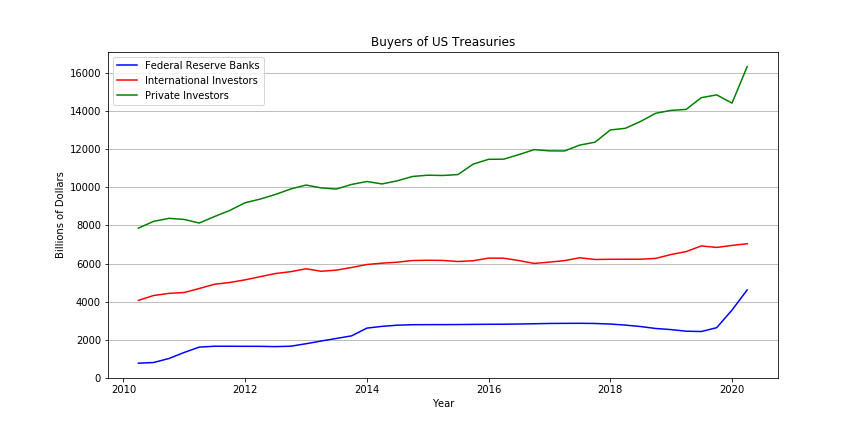

As the system currently exists, that debt has to go somewhere. As in someone has to buy it. As you can see below the amount of buying by foreign investors has not kept pace with the rate of holdings for domestic buyers and U.S. banks.

This probably reflects the standard risk-off trade of being long US bonds. The question here is to ask what will happen after the risk abates? If investors sell their safe assets and move into riskier assets, who or what will fill that gap in demand for all these treasuries? Perhaps the Federal Reserve will monetize it all and “write it off”.

Since the all that stimulus was effectively a bridge loan and was not used to finance future growth, one can reasonably expect that the debt will not pay for itself. But everybody knows that everybody knows that sovereign debt was never going to be paid back, at least in real terms. As it sits right now the government has become a significantly larger share in the economy. Reversing that it is not going to be an easy task. Whether that comes in the form of increased taxation or reduced federal spending doesn’t seem to be on the horizon. You would be hard pressed to find a politician besides the one or two crank that even cares about the federal debt much less be willing to do something about it. Even less so among the general public. If your in need of a laugh, during the last recession there was a fake movement created called “The Can Kicks Back”. Which was supposed to be a Millennials who were pissed off about the budgetary situation they are being left with. But why should we care about if our currency significantly depreciates when on average we have no assets and a fair amount of liabilities?

Enter MMT

Modern Monetary Theory, the economic theory that is a major part of the zeitgeist now. Modern Monetary Theory correctly explains how developed market currencies have worked since leaving the gold standard. Basically, the fiscal authorities are only really constrained by inflation. So fiscal policy (taxes, spending) should be used to finance projects (like the SR-71 Blackbird) and spending that may not have a positive return in the short run. The United States has been doing this for awhile now but instead of financing infrastructure, sustainable energy projects, and moonshot scientific research. You know things that will lead to positive growth. Instead we got two lost wars in the Middle East, transfer payments to ungrateful old people, and subsidies for big business. Surely if they could find $1 trillion to sink into Iraq, they could update the roads or literally anything else? MMT isn’t bad or good, it just is. I am going to do is tell you it needs to be a part of your investing framework going forward.

After WWII the Debt to GDP ratio was higher than it was now. Being the “Arsenal of Democracy” (while the Soviet Union drew fire) turned out to be expensive. The way that this debt was reduced was through a few factors: demographics, financial repression, debt financed positive-growth projects. Increasing the amount of humans that are around is the easiest way to increase productivity. No new technology or processes need to be developed. More people doing and consuming more stuff is inflationary all things being equal. Secondly, the Monetary Authorities kept real rates on government debt below 1% 2/3 of the time between 1945 and 1980. This facilitated a negative compounding effect on public debt to reduce the debt burden. Finally, projects like the Marshall plan and the effort to rebuild Japan did two things: provided markets for domestically produced goods and then once these societies were up and running became markets to outsource labor, reducing labor inflation pressures in the U.S.

Currently, we are not facing a population boom, in fact we are facing negative population growth. Additionally, due to the coronavirus pandemic nations and companies will seek to localize their supply chains in the name of robustness. Financial repression seems likely. How that might work is that the credit agencies will still rate U.S. debt as highly rated and the Banks and insurance companies and other bagholders will still be forced to buy it. Also, we could see the Federal Reserve go full yolo and monetize the difference in the Treasury’s issuance from what the bagholders don’t absorb. Historically, governments messing with the currency to that degree hasn’t worked out but who knows.

Conclusion

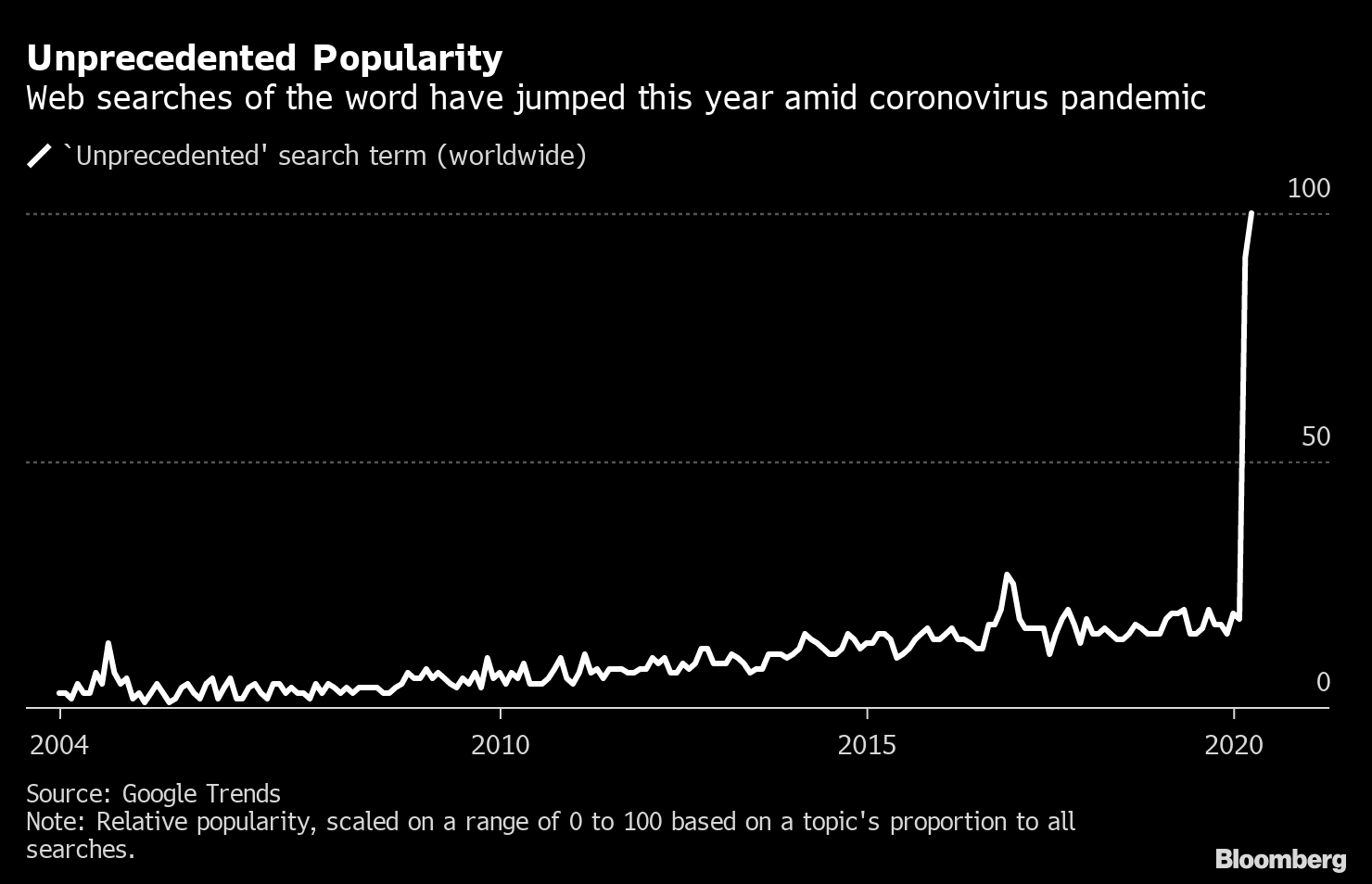

We truly live in unprecedented times. A lot of things are not going to return to how they were in 2019. That could be a good thing or a bad thing. Financial markets especially are probably going to be more volatile. In this type of environment passive investing and holding government bonds is probably not going to work out as well as they have in the past. When political concerns become superior to financial concerns you can bet that Treasurys are not the place to be. This has significant implications for asset allocation. The 60/40 and risk parity strategies that play off the convexity that government bonds provide during periods of instability will not work as well as they have before. I have previously wrote my views on asset allocation. The bond market vigilantes may return in our hour of need to restore the honor of American debt. I’m not holding my breath.

Disclaimer

This blog is for entertainment purposes and should not be taken as investment advice. Consult an investment professional before making investment decisions. I do not hold any certifications or licenses that allow me to give such advice. Secondly, here at alexnoonan.com we believe suckers get what they deserve. If you make a trade or invest without doing your own research and risk management and lose you have no one to blame but yourself.